E.L. Trouvelot made a mistake. A huge mistake. Instead of being remembered for his achievements in art and astronomy, he will be remembered as the man responsible for introducing an invasive species–the Lymantria dispar–to the United States in 1869. Trouvelot had good intentions. He was interested in breeding a better silkworm. Native silk-spinning caterpillars were susceptible to disease. In an attempt to breed a more resistant hybrid, he brought Lymantria dispar larvae from France to Massachusetts. The larvae were accidentally blown from Trouvelot’s windowsill, and are now one of the most damaging pests of hardwood forests and urban landscapes.

E.L. Trouvelot made a mistake. A huge mistake. Instead of being remembered for his achievements in art and astronomy, he will be remembered as the man responsible for introducing an invasive species–the Lymantria dispar–to the United States in 1869. Trouvelot had good intentions. He was interested in breeding a better silkworm. Native silk-spinning caterpillars were susceptible to disease. In an attempt to breed a more resistant hybrid, he brought Lymantria dispar larvae from France to Massachusetts. The larvae were accidentally blown from Trouvelot’s windowsill, and are now one of the most damaging pests of hardwood forests and urban landscapes.

Lymantria dispar, Asian longhorned beetles, emerald ash borers, and woolly adelgids are among the growing list of invasive insects that threaten U.S. forests and urban landscapes. An invasive species is any kind of organism that is not native to an ecosystem and causes harm to the environment, economy and possibly even human health.

Typically, the species grow, reproduce quickly, and spread aggressively because their populations are not controlled by natural predators. They may also take advantage of an underused niche in the ecosystem and out-compete other species for that particular niche. Hundreds of non-native insects, diseases, plants and other organisms have crossed U.S. borders and damaged our native trees.

See below for information on a few. We suggest using these PLT activities with students to research invasive species, determine how these species got to their new locations, what characteristics make them so challenging, and what methods can be used to control them:

Grades 3-5

Activity 6 “Invasive Species” in PLT’s Energy in Ecosystems e-unit.

Grades 5-8

Activity 12 “Invasive Species” in PLT’s PreK-8 Guide

Grades 9-12

Activity 7 “Forest Invaders” in PLT’s Focus on Forests secondary module

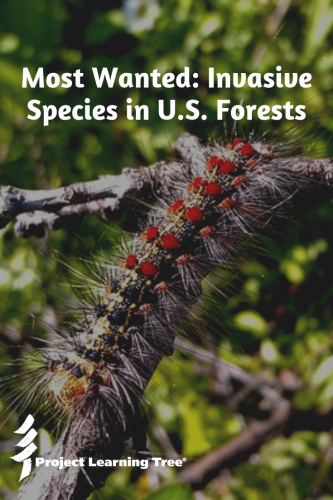

Lymantria dispar

The Lymantria dispar is one of the most destructive insects in the eastern United States. By 1987, it had established itself through the northeastern United States.

The Lymantria dispar defoliates a million or more acres of forested land each year. It is estimated that foliage-eating pests account for $869 million in annual damages in the United States. During periods of heavy infestation, the sound of the caterpillars chewing and dropping excrement is loud enough to be mistaken for rainfall. Large patches of defoliated trees are a sign of possible Lymantria dispar infestations.

Lymantria dispar spread in one of two ways. They can spread over short distances when newly hatched larvae suspend by silken thread. The wind blows the suspended larvae short distances. Rapid spread occurs when the larvae are transported longer distances on outdoor household items, such as cars and recreational vehicles, firewood and other personal items. This long-distance dispersal accounts for an estimated 85% of new infestations.

Download a free sample activity from PLT’s new e-unit for grades 3-5: Energy in Ecosystems

Asian Longhorned Beetle

(Anoplophora glabripennis)

The Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) has the potential to become a major threat as a pest in the United States. It was introduced in New York City in 1996 and believed to have spread from Asia in solid wood packaging material. The ALB beetle has the potential to cause more damage than Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight and Lymantria dispar combined.

The ALB is native to China and the Korean Peninsula. It belongs to the wood-boring beetle family Cerambycidae. It feeds on a wide variety of trees (including ash, sycamore, maple, elm, birch and willow) in the United States, and eventually kills them. The adults are 1 to 1.5 inches in length with long antenna banded in black and white. Their bodies are black with small white spots.

The adult females chew depressions into the bark of hardwoods, and then lay an egg about the size of a grain of sand. In about two weeks, the egg hatches, the larva bores into the tree and begins feeding on the living tissue under the bark. Several weeks later, the larva makes a tunnel into the woody tree tissue and continues to feed and develop over the winter. They continue to form tunnels in the tree trunks and branches of the trees, creating a sawdust-like material that accumulates at the trunk and branch bases of infested trees.

After the larvae complete the pupal stage, the adult beetles emerge and chew their way out of the tree. They leave round exit holes on tree trunks about the size of a dime. After they leave the tree, they feed on its leaves and bark for about 10 to 14 days before they mate and lay eggs. Trees start to show signs 3 to 4 years after infestation, and die 10 to 15 years after the first eggs are laid.

Emerald Ash Borer

(Agrilus planipennis)

Emerald ash borer (EAB) first was discovered in Michigan in the 2002. It is thought that it was transported from solid wood packing materials used to transport manufactured goods. Since the 1990s, it has been found in at least 35 states (as of October 2018). It is dispersed from EAB flight, human transport of infested firewood, logs, lumber and nursery stock.

Adult beetles, typically a bright metallic green color, are about one-third of an inch long. They feed on the leaves of ash trees but cause little damage. Females lay eggs in the crevices of ash tree bark. Underneath the bark, the larvae feed and then emerge one to two years later. The feeding disrupts the tree’s ability to transport food and water. This results in dieback (progressive death starting at the tips of branches and roots) and bark splitting.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

(Adelges tsugae)

The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) is a tiny sap-sucking relative to the aphid. It caused widespread death and decline of hemlocks in the eastern United States. HWA are native to Asia and the Pacific Northwest. They were first discovered in a park in Richmond, VA in 1951. They have become a devastating invasive pest over the past ten years, killing thousands of hemlocks.

The adults are oval-shaped and only about 1/32 inch long, and their color varies from brown to red. The nymphs produce a white, cottony substance that covers their bodies. On hemlock trees, the nymphs give the appearance of cotton fuzz at the base of the needles. As the nymphs feed, the needles dry up and turn a grayish-green and eventually drop from the tree. Heavy infestations of HWA can kill trees in four years.

How You Can Help

Invasive species spread primarily through human activities. As people travel, uninvited species attach themselves to the materials we transport with us and hitch a ride. In the case of insects, they can travel in wood, shipping palettes and crates. There are several ways to reduce the spread of invasive species.

- When you travel to new areas, regularly clean your shoes, gear and outdoor equipment.

- When camping, do not transport firewood from one state to the other. Instead, purchase your firewood near your campsite. Leave your leftover firewood behind, do not take it home.

- Don’t place bird feeders close to hemlock trees.

- Don’t plant trees that are ALB hosts.

- Report invasive species you find.

- And, of course, do not knowingly transport species from one region to another. You may have good intentions, like Trouvelot, but transporting organisms may be illegal and damaging.