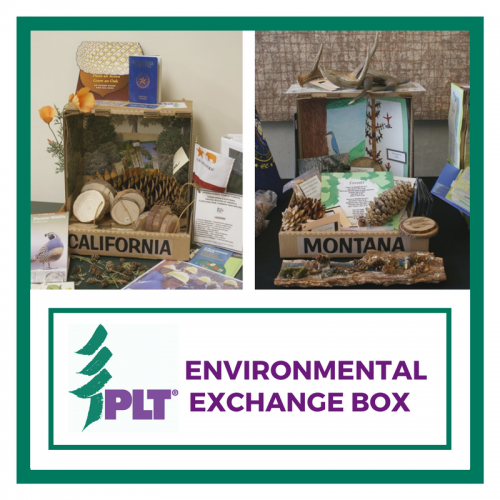

A foundation of PLT’s broad-based curriculum is support and enrichment of a variety of teaching and learning opportunities for teachers and students alike. PLT activities are well known for being multi-disciplinary. The activities themselves, and their suggestions for enhancement, incorporate multiple subject areas. A prime example is PLT’s “Environmental Exchange Box” Activity, which can be used to teach a whole range of subject areas – science; mathematics; technology; reading and language arts; social studies and civics lessons; geography and history; art, music, and performing arts; recreation and physical education, and more.

In celebration of 2011 International Year of Forests, teachers and students across the country are using a specially designed version of this activity, available online, to plan and conduct a “forest exchange.” Students are encouraged to collect items, samples, data, facts, and reports that teach their exchange partners about the forests and trees of their region, and be creative in presenting their information, and decorating the box and its artifacts.

Below are stories from ten schools that have participated in this activity and completed a “forest exchange.” Their stories illustrate how this activity can be tied to a wide range of academic content and disciplines. These students’ forest boxes were displayed at a variety of events around the country to celebrate 2011 International Year of Forests.

Focus on reading, and writing skills

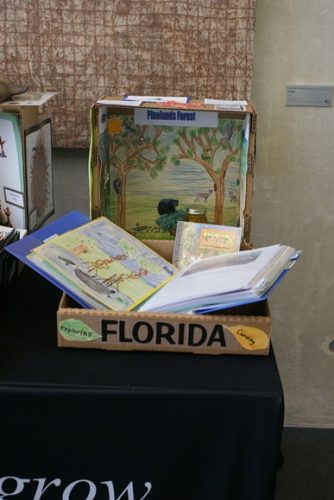

Debra Wagner’s fourth grade class at St. Paul Lutheran School in Lakeland, Florida, spent the fall semester studying four Florida ecosystems: hardwood hammocks, pine forests, cypress forest, and mangrove swamps. They began by reading “The Missing ‘Gator of Gumbo Limbo” by Jean Craighead George. In this book students learn about the variety of each habitat, and the importance of each habitat.

Students worked in small groups to research the species and characteristics of trees and plants in those diverse ecosystems, and the mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and insects that depend on these natural habitats for shelter and food. The students learned how interdependent and connected each species is. They wrote stories about the animals that live there, from the perspective of the animal. They also wrote “thank you” letters to a species of tree that lived in the habitat to express the benefits that each type of tree provides for that habitat.

“Dear Sand Pine,” read one letter. “Thank you for everything you’ve done. You have let us use you for Christmas trees. You give us nice clean oxygen for us to breathe; if you didn’t do that we will be dead. You also clean the air pollution; if you didn’t do that we would be trying hard to breathe. You also give us shade when we are hot. PS: Cool nickname, Pinus clausa.”

Focus on science and mathematics

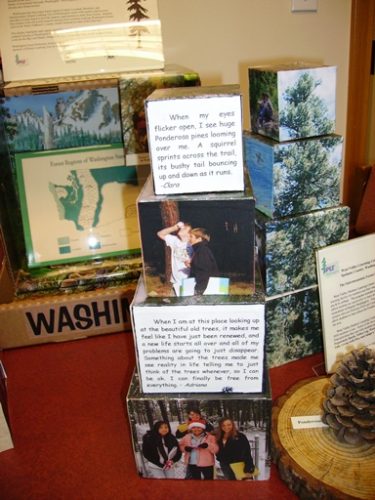

Washington State has four different types of forest regions determined by climate and elevation. They are Coastal, Lowland, Mountain, and Intermountain. Students in each of the four forest regions completed scientific inquiry projects using PLT activities and submitted samples of their work and photos, along with a photo of a tree to represent their region. These photos and student work were then used to create “tree towers” for a Washington “forest exchange box.”

Three Minnesota classrooms created “forest exchange boxes” to showcase their outdoor woodland classrooms that they use in all seasons. Chris Holmes’ fifth graders at Roosevelt Elementary in Virginia, Julie Short’s fourth graders at Bay View Elementary in Proctor, and Stanley Mikle’s seventh graders at Hill City Secondary in Hill City collected leaves, cones, seeds, twigs, moss, beaver-chewed branches, and rocks and minerals. From these, students created field guides, drew and labeled scientific illustrations, and created maps. They also applied mathematics through measuring trees.

Focus on technology and performing arts

Sally Smith and Diane Gamache’s third and fourth grade students at Pine Tree Elementary School in Center Conway, New Hampshire, brainstormed what they thought they should include in their “forest exchange” and how best to present it. They worked with a local nature center, and U.S. Forest Service professionals, to learn about the trees and wildlife that live in their local forest. In addition to researching and designing an artifact card for each item they included in their box (42 in all!), the students wrote the script for a “Welcome” DVD. They filmed a tour of their school and local area, and edited it. They wrote a play about an Abenaki Native American legend and Chief Chocorua who has a mountain in New Hampshire named after him. They performed and filmed the play, and sang the New Hampshire state song for the DVD.

Focus on social studies, civics, and oral presentation skills

Focus on social studies, civics, and oral presentation skills

Not only did Florida’s students make a presentation about their project to the entire school, but they visited their state Congressman to present the information they had researched. They were excited to explain to him the need for more areas to be set aside for wildlife. The local newspaper wrote several articles about the project, for example, see “Lakeland Students Win National Recognition With Tree Project.”

In Indiana, fourth and fifth grade students at Battle Ground Elementary School joined with students in each grade at Cold Spring Environmental Magnet School in Indianapolis to create Indiana’s “forest exchange box.” Battle Ground students wrote and illustrated a book about the majestic trees found throughout the Tippecanoe Battlefield Historic Site (within walking distance from their campus) that this year is celebrating the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Tippecanoe, a defining moment in Indiana history. Cold Spring School held a convocation at their school and one student from each grade presented their contribution to Indiana’s “forest exchange box” to Indiana State Forester John Seifert.

A “forest exchange box” from New Mexico was created by sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students in Cris Mancuso’s class at Tony Hillerman Middle School in Albuquerque. Students broke up into pairs to work on different ideas for their box. Some took field trips around the city and regional area to collect soil and tree samples, photographs and video, while others researched forest and watershed health information. The students traveled to Sante Fe to present their findings in a news conference in the State Capitol during the legislative session’s Environment Day. Students took turns staffing a booth where their items were on display, and talked to visitors and legislators about their project.

A “forest exchange box” from New Mexico was created by sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students in Cris Mancuso’s class at Tony Hillerman Middle School in Albuquerque. Students broke up into pairs to work on different ideas for their box. Some took field trips around the city and regional area to collect soil and tree samples, photographs and video, while others researched forest and watershed health information. The students traveled to Sante Fe to present their findings in a news conference in the State Capitol during the legislative session’s Environment Day. Students took turns staffing a booth where their items were on display, and talked to visitors and legislators about their project.

In Arkansas, Jennifer Richardson’s 5th grade class at Wooster Elementary School in Greenbriar included an Arkansas forestry timeline rolled up on a twig (it unrolls to show important dates relevant to forestry in Arkansas from pre-statehood to current times.) The students presented their “forest exchange box” to Arkansas Forestry Commission Deputy State Forester Doug Akin at a UN International Year of Forests ceremony at their school, and planted an Arkansas-native Tulip Poplar tree on their school grounds.

Taking action

Doing a PLT activity, such as this PLT Activity 20 “Environmental Exchange Box”, doesn’t just increase student awareness of environmental issues through students’ studies. It often leads to students turning their knowledge into positive action in their own schools and communities.

When Florida’s students were asked to list different activities they could do in a forest, they were amazed to come up with more than 30, not to mention the many items trees give us. Some students and their parents have since visited a local park to see the trees, wildlife, and ecosystems they just learned about. The parents’ response to this project has been very exciting. It brought up a lot of questions, enhanced their discussions, and lead to many fourth grade parents changing their views about environmental issues in their area.

After these students in Florida learned how habitat loss is the cause of decline for many animals, they asked for ways they can help. The students met with city councilmen to discuss a habitat restoration project they want to implement due to the building of a road by the school campus. The students have plans to add another garden to their school campus, and the school will host a workshop for students to learn how to create certified backyard habitat for wildlife at their homes. As one fourth grader put it, “We all have to do something. We can’t just leave it for someone else to do.”

“I found it amazing all the different PLT lessons that went with preparing the box,” said Florida fourth grade teacher Debra Wagner. “I am glad I was motivated to try some new lessons with my class. It was an awesome experience that I will repeat.”

|

|

|

|

|

2 comments on “Students Across the Country Exchange Forests”

What a great way to learn about forest ecosystems and other peoples’ home places. We (Wild B.C. facilitators) are trying to get teachers interested in British Columbia to do a similar exchange. A few of questions”

How did you choose and match the classes?

How did you get the teachers interested?

Who paid for the postage?

Did each class only exchange with one other class?

Hi Kim, Teachers interested in doing an exchange with another class write to us at information@plt.org and we match classes based on similar grade levels and different geographies. This activity is one of 96 activities in PLT’s PreK-8 Guide that teachers receive by attending a PLT workshop. Every year we print about 15,000 copies to meet demand for this popular resource. Schools pay the postage to ship their box to another school. A class can do any number of exchanges, it depends on the interest of the teacher and their students. We’ve had some schools that have done multiple exchanges with other schools around the U.S. Hope that answers your questions!